Between 2019 and December 2022, an extremely advanced iMessage vulnerability was in the wild that was eventually named “Operation Triangulation” by security researchers at Kasperksy who discovered it. Now, they’ve shared everything they know about the “most sophisticated attack chain” they’ve “ever seen.”

Today at the Chaos Communication Congress, Kaspersky security researchers Boris Larin, Leonid Bezvershenko, and Georgy Kucherin gave a presentation covering Operation Triangulation. This marked the first time the three “publicly disclosed the details of all exploits and vulnerabilities that were used” in the advanced iMessage attack.

The researchers also shared all of their work on the Kaspersky SecureList blog today.

The Pegasus 0-click iMessage exploit has been called “one of the most technically sophisticated exploits.” And Operation Triangulation looks to be at a similarly scary level – Larin, Bezvershenko, and Kucherin have said, “This is definitely the most sophisticated attack chain we have ever seen.”

0-day attack chain to 0-click iMessage exploit

This vulnerability existed until iOS 16.2 was released in December 2022.

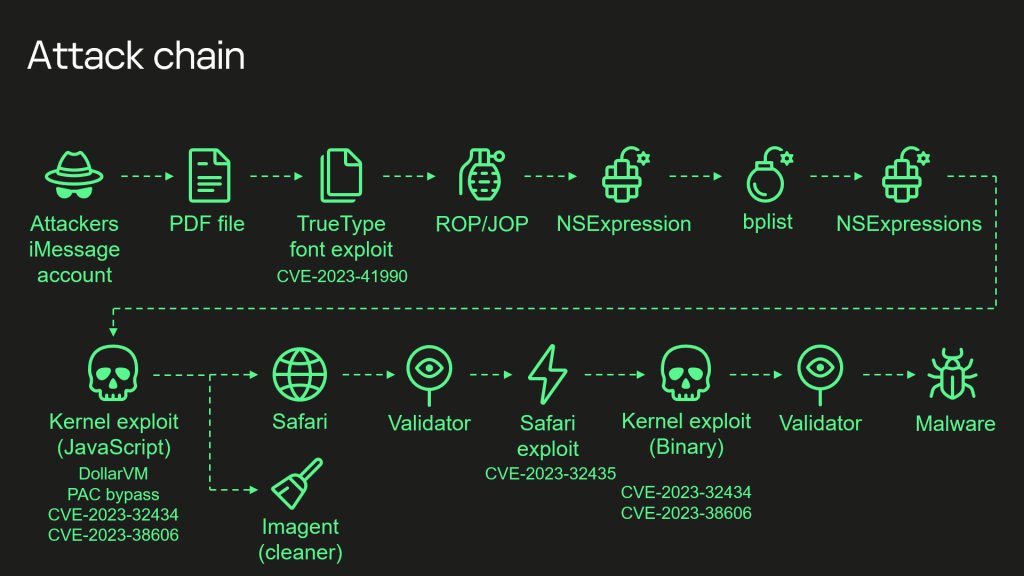

Here’s the full complex attack chain, including the four 0-days used to gain root privileges of a victim’s device:

- Attackers send a malicious iMessage attachment, which the application processes without showing any signs to the user.

- This attachment exploits the remote code execution vulnerability CVE-2023-41990 in the undocumented, Apple-only ADJUST TrueType font instruction. This instruction had existed since the early nineties before a patch removed it.

- It uses return/jump oriented programming and multiple stages written in the NSExpression/NSPredicate query language, patching the JavaScriptCore library environment to execute a privilege escalation exploit written in JavaScript.

- This JavaScript exploit is obfuscated to make it completely unreadable and to minimize its size. Still, it has around 11,000 lines of code, which are mainly dedicated to JavaScriptCore and kernel memory parsing and manipulation.

- It exploits the JavaScriptCore debugging feature DollarVM ($vm) to gain the ability to manipulate JavaScriptCore’s memory from the script and execute native API functions.

- It was designed to support both old and new iPhones and included a Pointer Authentication Code (PAC) bypass for exploitation of recent models.

- It uses the integer overflow vulnerability CVE-2023-32434 in XNU’s memory mapping syscalls (mach_make_memory_entry and vm_map) to obtain read/write access to the entire physical memory of the device at user level.

- It uses hardware memory-mapped I/O (MMIO) registers to bypass the Page Protection Layer (PPL). This was mitigated as CVE-2023-38606.

- After exploiting all the vulnerabilities, the JavaScript exploit can do whatever it wants to the device including running spyware, but the attackers chose to: (a) launch the IMAgent process and inject a payload that clears the exploitation artefacts from the device; (b) run a Safari process in invisible mode and forward it to a web page with the next stage.

- The web page has a script that verifies the victim and, if the checks pass, receives the next stage: the Safari exploit.

- The Safari exploit uses CVE-2023-32435 to execute a shellcode.

- The shellcode executes another kernel exploit in the form of a Mach object file. It uses the same vulnerabilities: CVE-2023-32434 and CVE-2023-38606. It is also massive in terms of size and functionality, but completely different from the kernel exploit written in JavaScript. Certain parts related to exploitation of the above-mentioned vulnerabilities are all that the two share. Still, most of its code is also dedicated to parsing and manipulation of the kernel memory. It contains various post-exploitation utilities, which are mostly unused.

- The exploit obtains root privileges and proceeds to execute other stages, which load spyware. We covered these stages in our previous posts.

The researchers highlight that they’ve almost reverse-engineered “every aspect of this attack chain” and will be publishing more articles in 2024 going in-depth on each vulnerability and how it was used.

But interestingly, Larin, Bezvershenko, and Kucherin note there is a mystery remaining when it comes to CVE-2023-38606 that they’d like help with.

Specifically, it’s not clear how attackers would have known about the hidden hardware feature:

We are publishing the technical details, so that other iOS security researchers can confirm our findings and come up with possible explanations of how the attackers learned about this hardware feature.

In conclusion, Larin, Bezvershenko, and Kucherin say that systems “that rely on ‘security through obscurity’ can never be truly secure.”

If you would like to contribute to the project, you can find the technical details on the Kaspersky post.